Italian Armed Forces

| Italian Armed Forces | |

|---|---|

| Forze Armate Italiane (FF.AA.) | |

Coat of arms of the Italian Defence Staff | |

| Founded | 4 May 1861 (163 years, 11 months) |

| Service branches | |

| Headquarters | Rome[1] |

| Leadership | |

| President of Italy | |

| Prime Minister | |

| Minister of Defence | |

| Chief of the Defence Staff | |

| Personnel | |

| Active personnel | 165,500[2] |

| Reserve personnel | 18,300[2] |

| Expenditure | |

| Budget | €31.3 billion (2025) ~$33,8 billion(ranked 12th)[3] |

| Percent of GDP | 1.5% (2024)[4] |

| Industry | |

| Domestic suppliers | Avio Beretta Fincantieri Fiocchi Munizioni Intermarine Iveco Leonardo Piaggio Aerospace |

| Foreign suppliers | |

| Annual imports | US$326 million (2014–2022)[5] |

| Annual exports | US$886 million (2014–2022)[5] |

| Related articles | |

| History | Military history of Italy Warfare directory of Italy Wars involving Italy Battles involving Italy |

| Ranks | Army ranks Navy ranks Air Force ranks Carabinieri Ranks |

The Italian Armed Forces (Italian: Forze armate italiane, pronounced [ˈfɔrtse arˈmaːte itaˈljaːne]) encompass the Italian Army, the Italian Navy and the Italian Air Force. A fourth branch of the armed forces, known as the Carabinieri, take on the role as the nation's military police and are also involved in missions and operations abroad as a combat force. Despite not being a branch of the armed forces, the Guardia di Finanza and Polizia di Stato is organized along military lines.[6] These five forces comprise a total of 340,885 men and women with the official status of active military personnel, of which 167,057 are in the Army, Navy and Air Force.[1][7][8][9] The President of Italy heads the armed forces as the President of the High Council of Defence established by article 87 of the Constitution of Italy. According to article 78, the Parliament has the authority to declare a state of war and vest the powers to lead the war in the Government.

History

[edit]

The military history of Italy chronicles a vast time period, lasting from the military conflicts fought by the ancient peoples of Italy, most notably the conquest of the Mediterranean world by the ancient Romans, through the expansion of the Italian city-states and maritime republics during the medieval period and the involvement of the historical Italian states in the Italian Wars and the wars of succession, to the Napoleonic period, the Italian unification, the campaigns of the colonial empire, the two world wars, and into the modern day, with world peacekeeping operations under the aegis of NATO, the EU or the UN. The Italian Peninsula has been a centre of military conflict throughout European history due to its geostrategic position: because of this, Italy has a long military tradition.

The Risorgimento movement emerged to unite Italy in the 19th century. The Kingdom of Piedmont-Sardinia took the lead in a series of wars to liberate Italy from foreign control. Following three Wars of Italian Independence against the Habsburg Austrians in the north, the Expedition of the Thousand against the Bourbons of the Two Sicilies in the south, and the Capture of Rome, the unification of the country was completed in 1871 when Rome was declared capital of Italy.

The presidential standard of Italy (Italian: Stendardo presidenziale italiano) is the distinctive standard of the presence of the President of Italy. The presidential standard is one of the National symbols of Italy. The standard recalls the colors of the flag of Italy, with particular reference to the standard of the historic Italian Republic of 1802–1805; the square shape and the savoy blue border, whose use was maintained even in the Republican era, symbolize the four Italian Armed Forces, which are commanded by the President of Italy.[14] Blue in heraldry also metaphorically symbolizes command.[15]

Organization

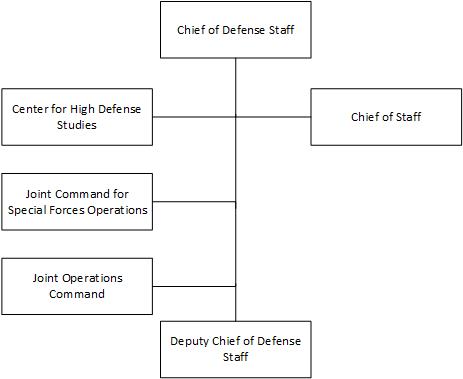

[edit]The office of the Chief of Defence is organised as follows:[16]

| Position | Italian title | Rank | Incumbent |

|---|---|---|---|

| Chief of the Defence Staff | Il Capo di Stato Maggiore della Difesa | Generale | Luciano Portolano |

| Deputy Chief of the Defence Staff | Sottocapo di Stato Maggiore della Difesa | Ammiraglio di Squadra | Giacinto Ottaviani[17] |

| Chief of Joint Operations | Il Comandante del Comando Operativo di Vertice Interforze | Generale di corpo d'armata con incarichi speciali | Francesco Paolo Figliuolo[18] |

The four branches of Italian Armed Forces

[edit]Italian Army

[edit]

The Italian Army (Italian: Esercito Italiano; abbreviated as EI) is the land force branch of the Italian Armed Forces. The army's history dates back to the Italian unification in the 1850s and 1860s. The army fought in colonial engagements in China and Libya. It fought in Northern Italy against the Austro-Hungarian Empire during World War I, Abyssinia before World War II and in World War II in Albania, Balkans, North Africa, the Soviet Union, and Italy itself. During the Cold War, the army prepared itself to defend against a Warsaw Pact invasion from the east.

Since the end of the Cold War, the army has seen extensive peacekeeping service and combat in Afghanistan and Iraq. Its best-known combat vehicles are the Dardo infantry fighting vehicle, the Centauro tank destroyer and the Ariete tank and among its aircraft the Mangusta attack helicopter, recently deployed in UN missions. The headquarters of the Army General Staff are located in Rome opposite the Quirinal Palace, where the president of Italy resides. The army is an all-volunteer force of active-duty personnel.

The Italian Army originated as the Royal Army (Regio Esercito), which dates from the proclamation of the Kingdom of Italy following the seizure of the Papal States and the unification of Italy (Risorgimento). In 1861, under the leadership of Giuseppe Garibaldi, Victor Emmanuel II of the House of Savoy was invited to take the throne and of the newly created kingdom.

The Italian Army has participated in operations to aid populations hit by natural disasters. It has, moreover, supplied a remarkable contribution to the forces of police for the control of the territory of the province of Bolzano/Bozen (1967), in Sardinia ("Forza Paris" 1992), in Sicily ("Vespri Siciliani" 1992) and in Calabria (1994). Currently, it protects sensitive objectives and places throughout the national territory ("Operazione Domino") since the September 11 attacks in the United States.

The army is also engaged in Missions abroad under the aegis of the UN, the NATO, and of Multinational forces, such as Beirut in Lebanon (1982), Namibia (1989), Albania (1991), Kurdistan (1991), Somalia (1992), Mozambique (1993), Bosnia (1995), East Timor and Kosovo (both in 1999), the Democratic Republic of the Congo (2001), Darfur (2003), Afghanistan (2002), Iraq (2003) and Lebanon again (2006).

Italian Navy

[edit]

The Italian Navy (Italian: Marina Militare, lit. 'Military Navy'; abbreviated as MM) is one of the four branches of Italian Armed Forces and was formed in 1946 from what remained of the Regia Marina (Royal Navy) after World War II. As of August 2014[update], the Italian Navy had a strength of 30,923 active personnel, with approximately 184 vessels in service, including minor auxiliary vessels. It is considered a multiregional and a blue-water navy.[19][20][21]

The navy of Italy was created in 1861, following the proclamation of the Kingdom of Italy. The new navy's baptism of fire came during the Third Italian War of Independence against the Austrian Empire. During the First World War, it spent its major efforts in the Adriatic Sea, fighting the Austro-Hungarian Navy. In the Second World War, it engaged the Royal Navy in a two-and-a-half-year struggle for the control of the Mediterranean Sea. After the war, the new Marina Militare, being a member of the North Atlantic Treaty Organisation (NATO), has taken part in many coalition peacekeeping operations. It is a blue-water navy. The Guardia Costiera (Coast Guard) is a component of the navy.

Today's Italian Navy is a modern navy with ships of every type. The fleet is in continuous evolution, and as of today oceangoing fleet units include: 2 light aircraft carriers, 4 amphibious assault ships, 3 destroyers, 11 frigates and 8 attack submarines. Patrol and littoral warfare units include: 10 offshore patrol vessels, 10 mine countermeasure vessels, 4 coastal patrol boats, and a varied fleet of auxiliary ships are also in service.[22] The flagship of the fleet is the carrier Cavour.

The ensign of the Italian Navy is the flag of Italy bearing the coat of arms of the Italian Navy. The shield's quarters refer to the four Medieval Italian Maritime Republics:

- 1st quarter: on red, a golden winged lion (the lion of St. Mark) wielding a sword (Republic of Venice)

- 2nd quarter: on white field, red cross, the Saint George's Cross (Republic of Genoa)

- 3rd quarter: on blue field, white Maltese cross (Republic of Amalfi)

- 4th quarter: on red field, white Pisan cross (Republic of Pisa)

The coat of arms is surmounted by a golden crown, which distinguishes military vessels from those of the merchant navy.

Italian Air Force

[edit]

The Italian Air Force (Italian: Aeronautica Militare; AM, lit. 'military aeronautics') is the air force of the Italian Republic. Since its formation, the service has held a prominent role in modern Italian military history. The acrobatic display team is the Frecce Tricolori. Italy was among the earliest adopters of military aviation. Its air arm dates back to 1884, when the Italian Royal Army (Regio Esercito) was authorised to acquire its own air component. The Air Service (Corpo Aeronautico Militare) operated balloons based near Rome.

In 1911, reconnaissance and bombing sorties during the Italo-Turkish War by the Servizio Aeronautico represented the first use of heavier-than-air aircraft in armed conflict. On 28 March 1923, the Italian Air Force was founded as an independent service by King Vittorio Emanuele III of the Kingdom of Italy.

During the 1930s, it was involved in its first military operations in Ethiopia in 1935, and later in the Spanish Civil War between 1936 and 1939. Eventually, Italy entered World War II alongside Germany. After the armistice of 8 September 1943, Italy was divided into two sides, and the same fate befell the Regia Aeronautica. The Air Force was split into the Italian Co-Belligerent Air Force in the south aligned with the Allies, and the pro-Axis Aeronautica Nazionale Repubblicana in the north until the end of the war. When Italy was made a republic by referendum, the air force was given its current name Aeronautica Militare. The cockade of Italy is one of the symbols of the Italian Air Force, and is widely used on all Italian state aircraft, not only military.[23]

Armed conflicts in Somalia, Mozambique and the nearby Balkans led to the Italian Air Force becoming a participant in multinational air forces, such as that of NATO over the former Yugoslavia, just a few minutes flying time east of the Italian Peninsula. The commanders of the Italian Air Force soon saw the need to improve the Italian air defences.

Carabinieri

[edit]

The Carabinieri (/ˌkærəbɪnˈjɛəri/, also US: /ˌkɑːr-/,[24][25] Italian: [karabiˈnjɛːri]; formally Arma dei Carabinieri, "Arm of Carabineers"; previously Corpo dei Carabinieri Reali, "Royal Carabineers Corps")[26][27][28][29] are the national gendarmerie of Italy who primarily carry out domestic and foreign policing duties. It is one of Italy's main law enforcement agencies, alongside the Polizia di Stato and the Guardia di Finanza. As with the Guardia di Finanza but in contrast to the Polizia di Stato, the Carabinieri are a military force. As the fourth branch of the Italian Armed Forces, they come under the authority of the Ministry of Defence; for activities related to inland public order and security, they functionally depend on the Ministry of the Interior. In practice, there is a significant overlap between the jurisdiction of the Polizia di Stato and Carabinieri, and both of them are contactable through 112, the European Union's Single Emergency number.[30] Unlike the Polizia di Stato, the Carabinieri have responsibility for policing the military, and a number of members regularly participate in military missions abroad.

The corps was instituted in 1814 by King Victor Emmanuel I of Savoy with the aim of providing the Kingdom of Sardinia, the forerunner of the Kingdom of Italy, with a police corps. It is therefore older than Italy itself. During the process of Italian unification, the Carabinieri were appointed as the "First Force" of the new national military organization. Although the Carabinieri assisted in the suppression of opposition during the rule of Benito Mussolini, they were also responsible for his downfall and many units were disbanded during World War II by Nazi Germany, which resulted in large numbers of Carabinieri joining the Italian resistance movement.

In 2000, they were separated from the Army to become a separate branch of the Italian Armed Forces. Carabinieri have policing powers that can be exercised at any time and in any part of the country, and they are always permitted to carry their assigned weapon as personal equipment (Beretta 92FS pistols). The Carabinieri are often referred to as "La Benemerita" (The Reputable or The Meritorious) as they are a trusted and prestigious law enforcement institution in Italy. The first official account of the use of this term to refer to the Carabinieri dates back to 24 June 1864.[31]

The new force was divided into divisions on the scale of one division for each province of Italy. The divisions were further divided into companies and subdivided into lieutenancies, which commanded and coordinated the local police stations and were distributed throughout the national territory in direct contact with the public. They carry out peacekeeping mission abroad, such as Kosovo, Afghanistan, and Iraq. At the Sea Islands Conference of the G8 in 2004, the Carabinieri were given the mandate to establish a Center of Excellence for Stability Police Units (CoESPU) to spearhead the development of training and doctrinal standards for civilian police units attached to international peacekeeping missions.[32]

Tomb of the Unknown Soldier

[edit]

The Tomb of the Italian Unknown Soldier (Italian: Tomba del Milite Ignoto) is a war memorial located in Rome under the statue of the goddess Roma at the Altare della Patria. It is a sacellum dedicated to the Italian soldiers killed and missing during war.

It is the scene of official ceremonies that take place annually on the occasion of the Italian Liberation Day (April 25), the Italian Republic Day (June 2) and the National Unity and Armed Forces Day (November 4), during which the President of the Italian Republic and the highest offices of the State pay homage to the shrine of the Unknown Soldier with the deposition of a laurel wreath in memory of the fallen and missing Italians in the wars.

The reason for his strong symbolism lies in the metaphorical transition from the figure of the soldier to that of the people and finally to that of the nation: this transition between increasingly broader and generic concepts is due to the indistinct traits of the non-identification of the soldier.[33]

His tomb is a symbolic shrine that represents all the fallen and missing in the war.[34] The side of the tomb of the Unknown Soldier that gives outward at the Altare della Patria is always guarded by a guard of honour and two flames that burn perpetually in braziers.[35]

The allegorical meaning of the perpetually burning flames is linked to their symbolism, which is centuries old, since it has its origins in classical antiquity, especially in the cult of the dead. A fire that burns eternally symbolizes the memory, in this case of the sacrifice of the Unknown Soldier moved by patriotic love, and his everlasting memory of the Italians, even in those who are far from their country: not by chance on the two perennial braziers next to the Tomb of the Unknown Soldier a plaque is placed whose text reads "Italians Abroad to the Motherland" in memory of donations made by Italian emigrants between the end of the 19th century and the beginning of the 20th century for the construction of the Vittoriano.[36]

International stance

[edit]

Italy has joined in many UN, NATO and EU operations as well as with assistance to Russia and the other CIS nations, Middle East peace process, peacekeeping, and combating the illegal drug trade, human trafficking, piracy and terrorism.

Italy did take part in the 1982 Multinational Force in Lebanon along with US, French and British troops. Italy also participated in the 1990–91 Gulf War, with the deployment of eight Panavia Tornado IDS bomber jets; Italian Army troops were subsequently deployed to assist Kurdish refugees in northern Iraq following the conflict.

As part of Operation Enduring Freedom, Italy contributed to the international operation in Afghanistan. Italian forces have contributed to ISAF, the NATO force in Afghanistan, and to the Provincial reconstruction team. Italy has sent 3,800 troops, including one infantry company from the 2nd Alpini Regiment tasked to protect the ISAF HQ, one engineer company, one NBC platoon, one logistic unit, as well as liaison and staff elements integrated into the operation chain of command. Italian forces also command a multinational engineer task force and have deployed a platoon of Carabinieri military police.

The Italian Army did not take part in combat operations of the 2003 Iraq War, dispatching troops only when major combat operations were declared over by the U.S. President George W. Bush. Subsequently, Italian troops arrived in the late summer of 2003, and began patrolling Nasiriyah and the surrounding area. Italian participation in the military operations in Iraq was concluded by the end of 2006, with full withdrawal of Italian military personnel except for a small group of about 30 soldiers engaged in providing security for the Italian embassy in Baghdad. Italy played a major role in the 2004–2011 NATO Training Mission to assist in the development of Iraqi security forces training structures and institutions.

Current Operations

[edit]

Since the second post-war the Italian armed force has become more and more engaged in international peace support operations, mainly under the auspices of the United Nations and European Union. The Italian armed forces are currently participating in 17 missions.[1]

United Nations

United Nations

European Union

European Union

- EUFOR Althea, since 2004 (Bosnia and Herzegovina)

- EUBAM Rafah, since 2005 (Gaza–Egypt border)

- EUNAVFOR Atalanta, since 2008 (Gulf of Aden)

- EUMM Georgia, since 2008 (Georgia, South Ossetia and Abkhazia)

- EULEX Kosovo, since 2008 (Kosovo)

- EUTM Somalia, since 2010 (Somalia)

- EUCAP Nestor, since 2012 (Indian Ocean)

- EUBAM Libya, since 2013 (Libya)

NATO

NATO

- KFOR, since 1999 (Kosovo)

- Operation Sea Guardian, since 2016 (Mediterranean Sea)

- Multilateral missions

- Operation Cyrene, since 2011 (Libya)

- MIADIT Somalia, since 2013 (Somalia and Djibouti)

Past Operations

[edit]The Italian armed forces participated in 10 operations since the second post-war.

United Nations

United Nations

European Union

European Union

- EUPOL Afghanistan, 2007 - 2016 (Afghanistan)

- EUCAP Sahel Niger, 2012 - 2024 (Niger)

- EUTM Mali, 2013 - 2024 (Mali)

- EUFOR RCA, 2014 - 2015 (Central African Republic)

NATO

NATO

- ISAF, 2001 - 2021 (Afghanistan)

- Operation Active Endeavour, 2001 - 2016 (Mediterranean Sea)

- Operation Ocean Shield, 2009 - 2016 (Gulf of Aden)

- Multilateral missions

- TIPH-2, 1997 - 2019 (West Bank)

- MIADIT Palestine, 2014 - 2023 (West Bank)

Gallery

[edit]-

Italian soldier with a Beretta ARX160 assault rifle.

-

Ariete tank during manoeuvres.

-

Centauro tank destroyer

-

Cavour aircraft carrier.

-

Freccia Infantry fighting vehicle.

-

Freccia Heavy Mortar Carrier.

-

Italian Navy F-35B Lightning.

-

Iveco LMV convoy.

-

A129 Mangusta attack helicopter.

-

The Salvatore Todaro (S-526) submarine.

-

Carabinieri Alfa Romeo Giulia

-

Carabinieri Iveco Daily, used for emergency intervention and transport of organs

-

Carabinieri motorcycle

See also

[edit]- List of Italian service weapons

- National Institute for the Honour Guard of the Royal Tombs of the Pantheon

- Uniforms of the Italian Armed Forces

- List of military equipment of Italy

Citations

[edit]- ^ a b c "Documento Programmatico Pluriennale per la Difesa per il triennio 2014-16" (PDF) (in Italian). Italian Ministry of Defence. 13 June 2014. Retrieved 8 January 2015.

- ^ a b IISS 2021, p. 116.

- ^ "Esplosione per le spese militari italiane: nel 2025 a 32 miliardi (di cui 13 per nuove armi)" (in Italian). milex.org. 2024-10-30. Retrieved 2025-03-06.

- ^ "La spesa italiana per la difesa: quanto lontani siamo dal requisito del 2% del Pil" (in Italian). osservatoriocpi.unicatt.it. 2024-11-29. Retrieved 2025-03-06.

- ^ a b "TIV of arms imports/exports data for India, 2014-2022". Stockholm International Peace Research Institute. 30 January 2024.

- ^ The Guardia di Finanza also operates a large fleet of ships, aircraft and helicopters, enabling it to patrol Italy's waters and to eventually participate in military scenarios

- ^ "Documento programmatico pluriennale per la Difesa per il triennio 2021-2023 - Doc. CCXXXIV, n. 4" (PDF). Ministry of Defence (Italy). 2021. Retrieved 6 June 2022.

- ^ Lioe, Kim Eduard (25 November 2010). Armed Forces in Law Enforcement Operations? - The German and European Perspective. Springer Science & Business Media. ISBN 9783642154348. Retrieved 28 March 2018 – via Google Books.

- ^ Schmitt, M. N.; Arimatsu, Louise; McCormack, Tim (5 August 2011). Yearbook of International Humanitarian Law - 2010. Springer Science & Business Media. ISBN 9789067048118. Retrieved 28 March 2018 – via Google Books.

- ^ Burgwyn, H. James (1997). Italian foreign policy in the interwar period, 1918–1940. Greenwood Publishing Group. p. 4. ISBN 0-275-94877-3.

- ^ Schindler, John R. (2001). Isonzo: The Forgotten Sacrifice of the Great War. Greenwood Publishing Group. p. 303. ISBN 0-275-97204-6.

- ^ Mack Smith, Denis (1982). Mussolini. Knopf. p. 31. ISBN 0-394-50694-4.

- ^ Paoletti, Ciro (2008). A Military History of Italy. Greenwood Publishing Group. p. 150. ISBN 978-0-275-98505-9.

... Ludendorff wrote: In Vittorio Veneto, Austria did not lose a battle, but lose the war and itself, dragging Germany in its fall. Without the destructive battle of Vittorio Veneto, we would have been able, in a military union with the Austro-Hungarian monarchy, to continue the desperate resistance through the whole winter, in order to obtain a less harsh peace, because the Allies were very fatigued.

- ^ a b "Lo Stendardo presidenziale" (in Italian). Retrieved 22 September 2010.

- ^ a b "Azzurri – origine del colore della nazionale" (in Italian). Retrieved 13 January 2025.

- ^ "Organigramma". www.difesa.it. Retrieved 28 March 2018.

- ^ "Sottocapo di Stato Maggiore della Difesa". www.difesa.it. Retrieved 25 April 2025.

- ^ "Il Comandante del Comando Operativo di Vertice Interforze". www.difesa.it. Retrieved 28 March 2018.

- ^ Todd, Daniel; Lindberg, Michael (May 14, 1996). Navies and Shipbuilding Industries: The Strained Symbiosis. Greenwood Publishing Group. ISBN 9780275953102. Retrieved May 14, 2018 – via Google Books.

- ^ Till, Geoffrey (2 Aug 2004). Seapower: A Guide for the Twenty-First Century. London: Routledge. pp. 113–120. ISBN 9781135756789. Retrieved 15 December 2015.

- ^ Coffey, Joseph I. (1989). The Atlantic Alliance and the Middle East. United States: University of Pittsburgh Press. p. 89. ISBN 9780822911548. Retrieved 30 November 2015.

- ^ "The Fleet – Marina Militare". marina.difesa.it. Retrieved May 14, 2018.

- ^ "San Felice, escursionista di Gaeta ferito mentre scende dal Picco di Circe" (in Italian). 17 April 2017. Retrieved 21 August 2018.

- ^ "carabiniere" (US) and "carabiniere". Lexico UK English Dictionary. Oxford University Press. Archived from the original on 2020-03-22.

- ^ "carabiniere". Merriam-Webster.com Dictionary. Merriam-Webster.

- ^ Paoletti, Ciro (2008). A Military History of Italy. Greenwood Publishing Group. ISBN 978-0-275-98505-9.

- ^ Stone, Peter G; Bajjaly, Joanne Farchakh (2008). The Destruction of Cultural Heritage in Iraq. Boydell & Brewer Ltd. p. 235. ISBN 978-1-84383-384-0.

- ^ Richard Heber Wrightson, A History of Modern Italy, from the First French Revolution to the Year 1850. Elibron.com, 2005

- ^ A new survey of universal knowledge. Vol. 4. Encyclopædia Britannica. 1952.

- ^ "The Service". NUE 112 Numero di emergenza Unico Europeo. Retrieved 2021-07-26.

- ^ "Benemerita". www.carabinieri.it.

- ^ G-8 Action Plan: Expanding global capability for peace support operations Archived 2010-10-09 at the Wayback Machine. Carabinieri, June 2004.

- ^ Tobia, Bruno (2011). L'Altare della Patria (in Italian). Il Mulino. p. 72. ISBN 978-88-15-23341-7.

- ^ "L'Altare della Patria" (in Italian). Archived from the original on 1 January 2018. Retrieved 1 January 2018.

- ^ "Il Vittoriano e piazza Venezia" (in Italian). 20 January 2015. Archived from the original on 6 June 2017. Retrieved 6 June 2017.

- ^ "Il mito della "lampada perenne"" (in Italian). 13 January 2010. Archived from the original on 12 February 2018. Retrieved 12 February 2018.

Sources

[edit]- International Institute for Strategic Studies (25 February 2021). The Military Balance 2021. London: Routledge. ISBN 9781032012278.

External links

[edit]- Official Site of Italian Ministry of Defense (in Italian and English)

- Official Site of Italian Army (in Italian and English)

- Official Site of Italian Navy (in Italian and English)

- Official Site of Italian Air Force (in Italian)

- Official Site of Carabinieri (in Italian)

- Official Site of Guardia di Finanza (in Italian)